Focusing on flow

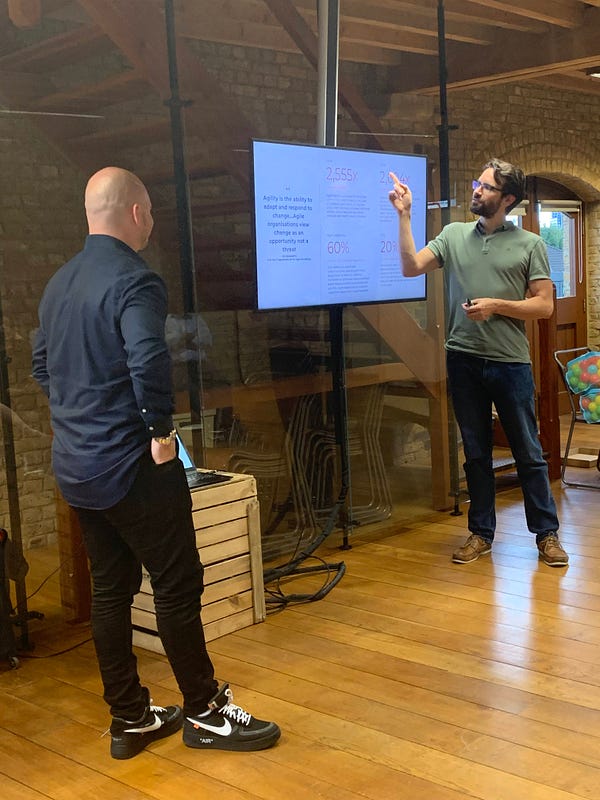

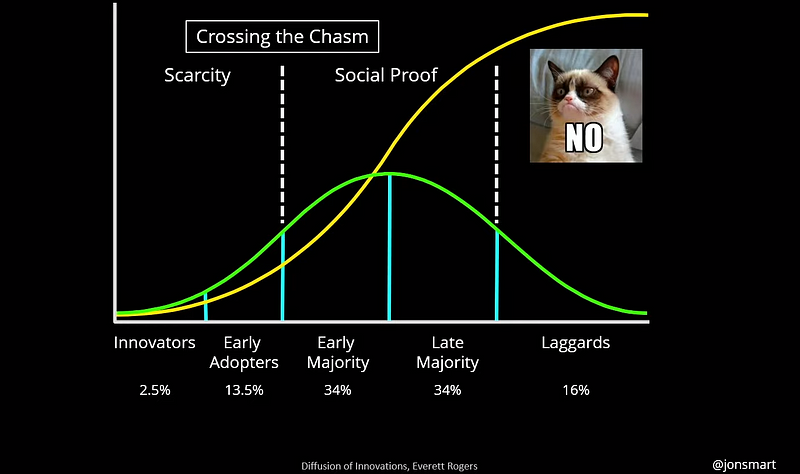

As a Ways of Working Enablement Specialist, one of our primary focuses is on flow. Flow can be referred to as the movement of value throughout your product development system. Some of the most common methods teams will use in their day to day are Scrum, Kanban, or Scrum with Kanban.

Optimising flow in a Scrum context requires defining what flow means. Scrum is founded on empirical process control theory, or empiricism. Key to empirical process control is the frequency of the transparency, inspection, and adaptation cycle — which we can also describe as the Cycle Time through the feedback loop.

Kanban can be defined as a strategy for optimising the flow of value through a process that uses a visual, work-in-progress limited pull system. Combining these two in a Scrum with Kanban context means providing a focus on improving the flow through the feedback loop; optimising transparency and the frequency of inspection and adaptation for both the product and the process.

Quite often, product teams will think that the use of a Kanban board alone is a way to improve flow, after all that is one of its primary focuses as a method. Taking this further, many Scrum teams will also proclaim that “we do Scrum with Kanban” or “we like to use ScrumBan” without understanding what this means if you really do focus on flow in the context of Scrum. However, this often becomes akin to pouring dressing all over your freshly made salad, then claiming to eat healthily!

Images via

/

/

If I was to be more direct, put simply, Scrum using a Kanban board ≠ Scrum with Kanban.

All these methods have a key focus on empiricism and flow — therefore visualisation and measurement of flow metrics is essential, particularly when incorporating these into the relevant events in a Scrum context.

The four flow metrics

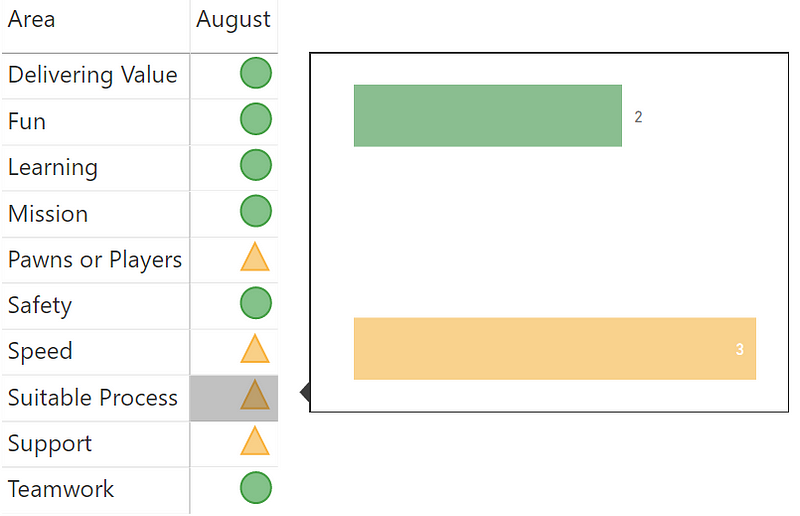

There are four basic metrics of flow that teams need to track:

Throughput — the number of work items finished per unit of time.

Work in Progress (WIP) — the number of work items started but not finished. The team can use the WIP metric to provide transparency about their progress towards reducing their WIP and improving their flow.

Cycle Time — the amount of elapsed time between when a work item starts and when a work item finishes.

Work Item Age — the amount of time between when a work item started and the current time. This applies only to items that are still in progress.

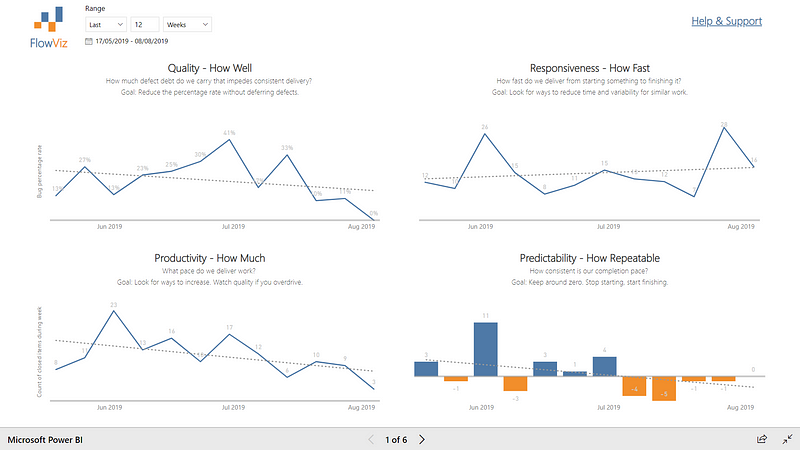

Generating these in ThoughtSpot

ThoughtSpot is what we use for generating insights on different aspects of work in Nationwide, one of the key products offered to the rest of the organisation by Marc Price and Zsolt Berend from our Measurement & Insight Accelerator. This can be as low level as individual product teams, or as high-level as aggregated into our different Member Missions. We produce ‘answers’ from our data which are then pinned to ‘pinboards’ for others to view.

Our four flow metrics are there as a pinboard for teams to consume, filtering to their details/context and viewing the charts. If they want to, they can then pin these to their own pinboards for sharing with others.

For visualizing the data, we use the following:

Throughput — a line chart for the number of items finished per unit of time.

WIP — a line chart with the number of items in progress on a given date.

Cycle Time — a scatter plot where each dot is an item plotted against how long it took (in days) and the completed date. Supported by an 85th percentile below showing how long in days items took to complete.

Work Item Age — a scatter plot where each dot is an item plotted against its current column on the board and how long it has been there. Supported by the average age of WIP in the system.

Using these in Scrum Events

Throughput (Sprint Planning, Review & Retrospective) — Teams can use this as part of Sprint Planning in forecasting the number of items for the Sprint Backlog.

It can also surface in Sprint Reviews when it comes to discussing release forecasts or product roadmaps (although I would encourage the use of Monte Carlo simulations in this context — more in a later blog on this). As well as being reviewed in the Sprint Retrospective, where teams inspect and adapting their processes to find ways to improve (or validating if previous experiments have improved) throughput.

Work In Progress (Daily Scrum & Sprint Retrospective) — as the Daily Scrum focuses on what’s currently happening in the sprint/with the work, WIP chart is good to look at here (potentially seeing if it’s too high).

The chart also is a great input into the Sprint Retrospective, particularly seeing where WIP is trending towards — if teams are optimising their WIP then you would expect this to be relatively stable/low — if high/highly volatile then you need to “stop starting and start finishing” or find ways you can improve your workflow.

Cycle Time (Sprint Planning, Review & Retrospective) — Looking at 85th/95th percentiles of Cycle Time can be a useful input into deciding what items to take into the Sprint Backlog. Can we deliver this within our 85th percentile time? If not, can we break it down? If we can, then let’s add it to the backlog. It also works as an estimation technique, so stakeholders know that when work is started on an item, there is an 85% likelihood it will take n days — want it in n days? Ok well that’s only got a 50% likelihood, can we collaborate to break it down into something smaller? Then let’s add that to a backlog refinement discussion.

In the Sprint Review it can be used by looking at trends, such as if your cycle times are highly varied then are there larger constraints in the “system” that we need stakeholders to help with? Finally, it provides a great discussion point for Retrospectives — we can use it to deep dive into outliers to find out what happened and how to improve, see if there is a big difference in our 50th/85th percentiles (and how to reduce this gap), and/or see if the improvements we have implemented as outcomes of previous discussions are having a positive impact on cycle time.

Work Item Age (Sprint Planning & Daily Scrum) — this is a significantly underutilised chart that so many teams could get benefit from. If you incorporate this into your Daily Scrums, it will likely lead to much more conversations on getting work done (due to item age) rather than generic updates. Compare work item age to your 85th percentile on your cycle time — is it likely to exceed this time?

Is that ok? Should we/can slice it down further to get some value out there and faster feedback sooner? All very good, flow-based insights this chart can provide.

It may also play a part in Sprint Planning — do you have items left over from the previous sprint? What should we do with those? All good inputs into the planning conversation.

Summary

To summarise, focusing on flow involves more than just using a Kanban board to visualize your work. To really take a flow-based approach and incorporate the foundations of optimising WIP and empiricism, teams should utilise the four key flow metrics of Throughput, WIP, Cycle Time and Work Item Age. If you’re using these in the context of Scrum, look to accommodate these appropriately into the different Scrum events.

For those wanting to experiment with these concepts in a safe space, I recommend checking out TWiG — the work in progress game, (which now has a handy facilitator and participant guide) and for any Nationwide folks reading this curious about flow in their context, be sure to check out the Four Key Flow Metrics pinboard on our ThoughtSpot platform.

Further/recommended reading:

Kanban Guide (Dec 2020 Edition) — KanbanGuides.org

Kanban Guide for Scrum Teams (Jan 2021 Edition) — Scrum.org

Basic Metrics of Flow — Dan Vacanti & Prateek Singh

Four Key Flow Metrics and how to use them in Scrum events — Yuval Yeret